Google “Will Whitehorn” and you’ll often find him described as Sir Richard Branson’s “right-hand man”; the guy that help steer the Virgin brand through good and bad times, and developed its approach to honest PR. Whitehorn enjoyed a 25-year career with Virgin, working across many of its companies before ultimately becoming the President of Virgin Galactic in 2004. It was an ambitious project. Perfect for a man with a deep passion for engineering, innovation running through his veins and an insatiable appetite for life.

Wikipedia claims Whitehorn was “talent spotted” by Branson, so we were keen to learn what it was like to be courted and interviewed by one of the world’s most celebrated entrepreneurs and businessman, what he learnt about recruiting Virgin’s way, how on earth he built Virgin Galactic’s original team, and what he looked for when hiring its first engineers. We caught up with Will while he was relaxed, on holiday in Antigua, and the first thing that hit us was his infectious enthusiasm…

You spent over 20 years at Virgin, what was it like to work there?

I joined Virgin in 1987 and it was very different in those days. Peoples’ initial reaction was, well, in truth I think they thought I was a bit mad to work with a music company that had just started an airline – with only one plane! So, they were sceptical about the company’s future, and whether or not it would be a success.

At that time, there were around 60 people in Virgin’s head office, so it was a much smaller organisation than it is now. There are now something like 70,000 to 80,000 Virgin employees worldwide.

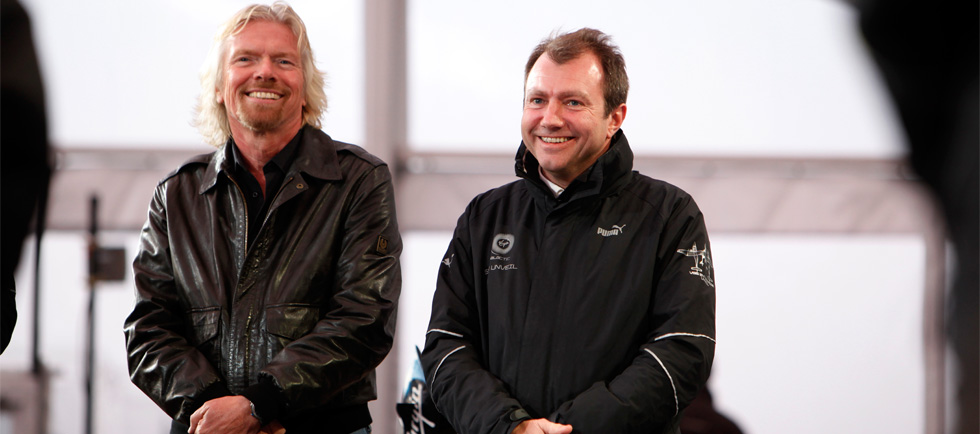

Source: Image supplied by Will Whitehorn.

Is it true that you were headhunted by Sir Richard Branson himself?

Not quite, no. I was first approached by the Managing Director of Virgin, Donald Cruickshank, about a new role dealing with Virgin’s corporate affairs and financial journals. I was initially interviewed by Donald, then by the Finance Director, and then by two other individuals beneath him. Then last, but certainly not least, by Branson himself.

My interview with Richard was in his house and his little boy, who must have been nine at the time, stood behind Richard during the whole interview. He [Richard] asked me a lot of questions around what I thought about Virgin, my thoughts on where the company should go and what they should do.

I then talked in-depth about how Virgin was a difficult company to place on the stock market, especially in those days, and I asked him if he felt he had done this slightly prematurely. We then talked about the work I’d done at Thomas Cook, my experience with flying helicopters on the North Sea oil rigs, and finally my past experience doing search and rescue work for British Airways. He commented “that will come in handy as I’m planning to fly a balloon across the Atlantic.” And the rest is history!

Did you learn anything by being interviewed by him?

It was a completely new experience being interviewed in someone’s home, and in such a relaxed environment. It was an eye opener for me, that interviews didn’t always have to be so formal.

What was it about Virgin that appealed to you?

I was 27 years old and I was being given an opportunity to work at a very different sort of organisation, which really appealed. I was interviewed in Branson’s front room with his little boy running around, for an exciting role where I wouldn’t have to sit in a suit behind a desk. You have to remember that, In 1987, that was a very rare thing. In the early ‘90s, most people were expected to wear a suit and tie every morning.

Branson aside, did working at Virgin for almost 20 years teach you anything unique about recruiting, people, and culture?

Yes, definitely. One of the things that I found very interesting about Virgin was employee loyalty. It was a ‘job for life’ so to speak, where people tended to stay for a very long period of time. Take me, for example. I worked there for 20 years full time as Virgin’s Corporate Director, responsible for brand development. Then another five years on top of that part time as president of Virgin Galactic.

There was a very low staff turnover. The few that left after a short period of time, didn’t like the fact that you had to make your own work; Virgin gave its employees a huge amount of autonomy, which was very rare in the early ‘90s, making them an extremely unique organisation.

When he started the business, Branson believed very much in taking people out of an existing business and giving them the responsibility, authority, and means to start a new business within Virgin. As an entrepreneur, he thought that this was the right way to do things. He would just give people the responsibility to solve a problem and if you were somebody that enjoyed that – and I certainly was – it was great. I think was this level of autonomy and genuine investment in people that caused such a low staff turnover.

However, there were some that just wanted to be told what to do who didn’t want to have to think, these were the type that would often leave quite soon.

So, when recruiting, I learnt that it’s crucial to be clear with people as to what they’re going to be doing when they’re starting a new role. You have to be clear as what their responsibilities are.

Don’t just assume that the people you are interviewing are the same as you in their motivations or behaviours. It doesn’t mean they won’t fit in – we’re all different – but being clear in your expectations helps you find out if they are right for the role, or not.

Today, the likes of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have joined Virgin Galactic in the commercial space race, but in the early ‘00s Virgin were pioneers. How on earth did you recruit the first engineers to join the programme when the industry simply did not exist at the time?

The space project began properly in 2004, when we bought the rights to the technology, science and development of building our own spaceship from a man called Paul Allen, who had been Bill Gates partner at Microsoft. Allen had just won a $10m prize for building the world’s first private spaceship.

So, we started by buying the rights to the technology and began building the first Virgin galactic spaceship in 2007. As president of Virgin Galactic, I was in charge of managing the team that built the space plane and it was a very interesting experience to say the least.

It was the first of its kind to be built so, obviously, you weren’t able to recruit individuals from existing companies who had previous experience on a project like this, because there were no other projects like this! It’s not like building a new car where you can poach a skilled workforce from existing car companies. So, I needed to recruit people from different places.

Whenever you start an innovative project, it’s always good to look back in history. I found that at the end of the second world war, nobody knew how to build jet planes. An American man called Kelly Johnson wanted to build one of the world’s first jet fighters and so he set up ‘Kelly’s 14 Rules of Management’, which even 80 years later you can find on Google. I used those rules to guide me, and I recruited people in the early stages who I knew could manage difficult, “special” projects.

I began by recruiting a guy called Jonathan Firth, who was a very good Project Director at Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Trains. He then recruited some good quality engineers.

I then had to think about the commercial side of the project, and act as a commercial operator in a world that didn’t have commercial operators. It was crucial that we started selling satellite launches and space tourist tickets. Therefore, I recruited a guy called Steven Attenborough as Commercial Director, he’d worked with very high net worth individuals in the financial service industry.

Finally, we needed someone to take control of event management. We didn’t want to use an events management company because of how unique the project was. So, I turned to a lady called Susan Newson, who had really good experience working on event planning for very big companies around the world.

I then recruited a guy called George Whiteside, who had been the Chief of Staff at NASA. George then began to use his recruiting techniques. I never used head hunters to start with. Simply because in the early days there wasn’t much precedent for what we were doing, so I tended to recruit people who had a very good expertise in an area that would probably be complimentary.

So how did it work out?

Very well. When you look back, at the early stages, there were just a few people that formed the team, so we needed these key figures to lead the way in their respective field of expertise.

Given you were first, do you think it was easier for Jeff and Elon to recruit and build their teams for Blue Origin and SpaceX?

Elon Musk was doing something different to Virgin. He was building a rocket that launched from the ground rather than a space plane that launched in the air. For Musk, it was much easier to recruit people because he was building a modern version of a traditional rocket. He also had an advantageous location, as he was based off the coast of California, whereas we were based in Texas.

Jeff Bezos, on the other hand, will have found it harder to recruit, as Blue Origin were also based in Texas, which had a limited supply of skilled candidates.

Were people surprised when Virgin Galactic reached out to them?

Yes, very! At the same time, I got approached by a lot of interesting people that wanted to work on the project. So I had no shortage of people to fill certain roles.

Did you have a clear brief of the skills you needed, and job descriptions for every role, or did you have to play it by ear with the talent that was available on the market?

That’s an interesting question. Yes, I had a clear brief of the skills that were needed. People had to be at the top of their game of whatever it was I was recruiting for, be it engineering, commercial development, marketing, or event management.

Job descriptions were very difficult to create, though, given the early nature of the project – we needed everyone to be flexible.

Did you utilise psychometric or aptitude tests?

Virgin does use these tests now but, in the early days, no.

Did you lose people in those early days, or did the first hires generally stick with the project?

We didn’t lose anybody in the very early stages, no.

What was your best and worst hire for the Virgin Galactic project?

I can confidently say, that in the early days when I was there, we didn’t make any bad hires. We had one individual we recruited from a satellite manufacturing company, who was very good at his job, but found it hard to fit into the culture and lack of strict structure in the company. But, from a team of 50, he was just one that didn’t work out.

And who would you say was your best hire?

There were two top hires. The first, a man named Jonathan Firth, our Project Director, did a fantastic job at directing the build for the first spaceship.

The second, Susan Newson, was incredibly good at organising everyone in the company, and did a brilliant job of organising our promotional business events.

After leaving Virgin Galactic you’ve worked on a number of really innovative and market-disrupting projects, from autonomous vehicles to Purplebricks, the online estate agency. Do you think these companies have an advantage when recruiting, because they’re different and exciting?

Purplebricks has been fascinating. I only got involved in Purplebricks as a Non-Executive Director. When the company first began, I helped the Bruce Brothers [the founders, Michael and Kenny] recruit the first member of their marketing team, James Kydd, who is now also working with Hiring Hub.

Kydd was the top of his game at Virgin, and was responsible for Virgin Atlantic and Mobile, before becoming the Brand Director of Virgin Media. Purplebricks’ is changing the face of the estate agent industry in the UK and it’s this type of market-disruptive, innovative business that attracts talent like James when they’re at the top of their game.

Another market disruptive project I’ve been involved in is a Clyde Space, who manufacture miniature space satellites.

I find businesses like these – both in their growth phase – really interesting. You simply can’t follow the same rules of recruitment that you do with a business that’s in a mature phase. When a business is mature, you know exactly what roles need fulfilling, so you are able to create a very detailed job description, create structures, and of course pay grades. Once you’ve got that it’s easy. The hardest stage is the transition from start-up to the mature phase, when the business is growing. Most rely on recruiters during that phase.

Given that you’re a champion of innovation and you’ve always worked on projects that push industries forward, what are your thoughts on Hiring Hub’s approach to the recruitment agency model?

I met Simon Swan when I was doing a talk on innovation for a financial services company. Simon and I got chatting and he described Hiring Hub’s business model to me and, personally, I think it’s very exciting. The idea of taking recruitment away from where it has been in the past, where there are tens of thousands of small recruitment companies that don’t, or can’t, make the best use of technology, people, or marketing, is fantastic. It’s an industry that’s ready for change and Simon knows this. He has got a fantastic model for Hiring Hub and I’m certain the business is going to be very successful.

Want to discover how the firms like Virgin, Travelex, The Hut Group, Box, and EE determine candidate fit? Get your FREE copy of our ‘Ultimate Guide to Interviews’ here to find out more.